Friedrich Nietzsche posits that “we shall have gained much for the science of aesthetics when we have come to realize… that the continuous evolution of art is bound up with the duality of the Apolline and the Dionysiac” (Leitch 740).

Aesthetics in this context means “as ‘pertaining to sense perception’”–how feeling is manipulated based on the stimuli offered and received (737). And while “sense perception” can be considered from the perspective of what “our sensations indicate [about ourselves and] our lives”, Nietzsche was specifically concerned with the “art” itself and what it meant for “the artist/creator” as well as their “struggle to bend [its form] to his or her will” (738).

The dichotomy created through the “deities of art, Apollo and Dionysos”, as explained by Nietzsche, presents “an enormous opposition, both in origin and goals, between the Apolline art of the image-maker… and the imageless art of music [Dionysos]” (741). But the “different drives [can] exist side by side… in conflict”; when “they appear paired…”, they forge “a work of art” (741).

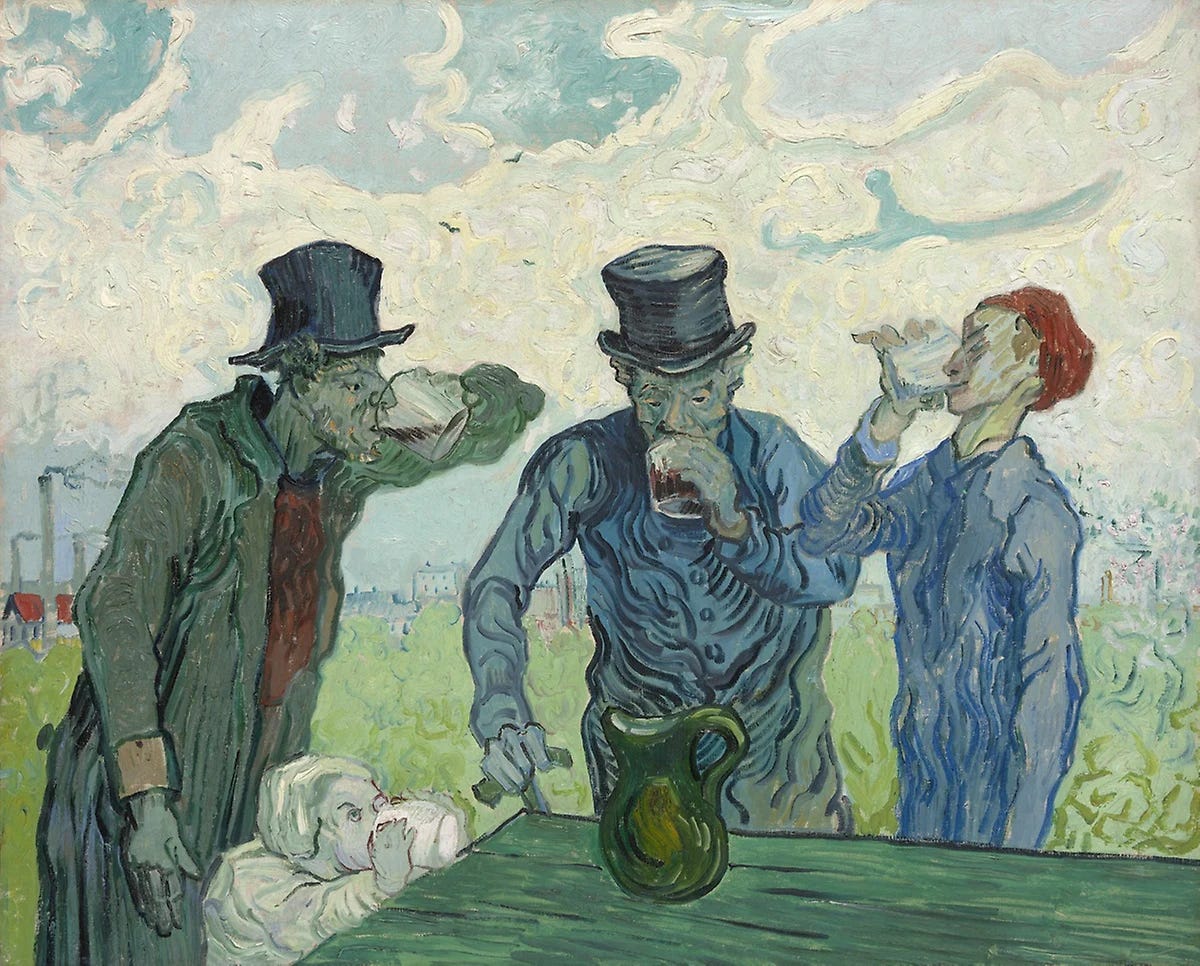

The separation is a fine line, which akins “the separate art-worlds [of Apollonian and Dionysian to] dream and intoxication”, respectively (741).

Singer/Songwriter/Actress, Ariana Grande, started her career when she was fifteen, performing on Broadway before moving into television. She eventually signed with Republic Records and debuted her first album, Yours Truly, two years later.

Nietzsche wrote that “an artist [creates] worlds of dream” and that “the lovely semblance of dream is the precondition of all the arts… including [ ] an important half of poetry” (741). He finds “clear evidence that… common to all our lives” is this desire to “experience the state of dreaming with profound pleasure and joyous necessity” (742).

I remember being 10 years old when Grande’s album came out. I only really knew her as an actress and was barely aware of the other aspects of her fame.

But the first track of Yours Truly changed a lot about my perception of her.

Honeymoon Avenue is timeless for many reasons.

The track opens with a theatrical swell, the vibrant sound of ascending strings dancing over top a melody composed of 16th notes working in repeated phrases arrayed using rapid half and whole steps to produce both a winding and whimsical effect.

Dream-like the track seems; and the atmosphere only deepens from there.

The first percussive sound is not made by an instrument. Grande opts for a more acapella feel; and, quite anachronistically, the collection of voices present in a doo-wop-like style, with a classic “shoo-doo-doo-mmm-dooo” sound that is quickly answered by a “da-daa” (Grande 0:15). Fingers snap two seconds later, serving as the only other percussive element in the first twenty seconds of song.

Grande does not neglect spatial stimuli. She takes us out of the theatre and onto the road, the atmosphere shifting through the sounds of traffic. Car horns and other ambient sounds, reminisce of bustling streets and city life, force further depth–plunging the listener deeper into the Apollonian dream.

But perhaps, too deep, for the immersive dream, when sunken into too far, crosses into the Dionysian intoxication.

Nietzsche explains that the “delicate line which the dream-image may not overstep…[can] deceive us as if [the dream] were crude reality” (Leitche 742). The highest form of art as strictly Apollonian is found in the “principium individuationis”, which describes the moments when a “thing” is still distinct from other “things”–that is, when there is still the possibility of finding “intense pleasure, wisdom and beauty [in] ‘semblance’” (743).

In this sense, when considering art, “enormous horror seizes people when they suddenly become confused and lose faith in the cognitive forms… [because they] appear to sustain [ ] exception” (743).

Grande’s fluidity of form, weaved smoothly and without awkwardness to alarm the listener to the multiple forms pulled from different epochs of music, is this loss of understood or accepted “form”. Nietzsche states that when “this breakdown of the principium individuationis occurs, we catch a glimpse of the essence of the Dionysiac, which is best conveyed by the analogy of intoxication (743).

Yet, the dream-like intoxication of Honeymoon Avenue displays an occurrence of togetherness, one that does not portray “conflict” but, instead, a “paired” appearance (741).

All of the moves layered into Grande’s song production can be delineated, recognized with the intention to decipher and differentiate. When taken in all at once with the intention to be lost, the intoxication is available to the listener, who when unfocused on specific elements, is able to dip in and out of the dream into the state of intoxication. These are the “aesthetics” of the “art”, as Nietzsche would describe:

There is an atmospheric construction resembling:

a theatre-like ambience with the opening string ensemble followed by

street sounds of city life created through car horns and background noise

There is intentionality in time manipulation:

Doo-wop, present in the song, was a genre popular in the 1950s/60s.

The beat itself is largely a mix of both funk and pop, but it is varied by hip hop/r&b influences.

The presence of strings present a timeless aspect to the music, having been a musical presence available in a variety of spaces.

These spatial shifts that Grande compounds with the temporal ambiguity of mixing older vocal styles with more contemporary sounding strains are all carefully chosen stimuli. This, to me, feels similar to the idea of “struggle [in] bend[ing form]” that Nietzsche’s Apollonian/Dionysian split begs for in creative invention (Leitch 738).

Similarly, the innovative and inimitable storytelling of J.R.R. Tolkien mirrors this in-between state of intoxicative/dream-like art that Grande achieves through her music and Nietzsche seeks in the best of aesthetics.

Many critics wonder what sets apart Tolkien’s prose, for it is plainly seen the influences that Tolkien incorporates without vagueness to his narrative, yet his work is markedly unique.

Evidence of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight are littered throughout the volumes. From descriptions of characters to reprising scenery and events, Tolkien’s work is the epitome of fanfiction.

Here are a few examples:

From the First Fitt of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight:

Scene: The Green Knight speaks to the King Arthur and the Round Table at their Christmas feast ~

“If a person here present, within these premises,

is big or bold or red blooded enough

to strike me. . . / So who has the gall? the gumption? the guts?” (Armitage 39, lines 285-291)

and

“‘So here is the House of Arthur,’ he scoffed,

who virtues reverberate across vast realms . . .

breathtaking bravery and the big-mouth bragging?

The towering reputation of the Round Table,

skittled and scuppered–what a scandal!” (Armitage 41, lines 309-314)

VS.

From Chapter 10 “The Black Gate Opens” in Book 5 of Lord of the Rings:

Scene: the “Mouth of Sauron”, Lieutenant of the Tower of Baradûr, speaks when he meets the Company at Gondor (Gandalf, Aragorn, Pippin) ~

‘Is there anyone in this rout with authority to treat with me?’ he asked. ‘Or indeed with wit to understand me? Not thou at least!’ he mocked, turning to Aragorn with scorn. ‘It needs more to make a king than a piece of Elvish glass, or a rabble such as this. Why, any brigand of the hills can show as good a following!’

Aragorn said naught in answer, but he took the other’s eye and held it. (Tolkien 888-889)

From Beowulf:

Scene: Beowulf before fighting the dragon ~

The veteran king sat down on the cliff-top.

He wished good luck to the Geats who had shared

his hearth and his gold. He was sad at heart,

unsettled yet ready, sensing his death.

His fate hovered near, unknowable but certain:

it would soon claim his coffered soul,

part life from limb. Before long

the prince's spirit would spin free from his body. (Donoghue & Heaney 2417-2424)

VS.

From Chapter 10 “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields” in Book 5 of Lord of the Rings:

Scene: Théoden rides into battle, leading the charge ~

Théoden could not be overtaken. Fey* he seemed, or the battle-fury of his fathers ran like new fire in his veins, and he was borne up on Snowmane like a god of old, even as Orome¨ the Great in the battle of the Valar when the world was young. (Tolkien 838)

* Fey meaning “marked by a foreboding of death or calamity” , the Germanic origin of the word being Old English fǣge (in the sense ‘fated to die soon’)

From Beowulf

Scene: Queen Wealhtheow as Cupbearer for the Hall

The Queen spoke:

“‘Enjoy this drink, my most generous lord;

raise up your goblet, entertain the Geats

duly and gently, discourse with them,

be open-handed, happy and fond.

Relish their company, but recollect as well

all of the boons that have been bestowed on you…’

… The cup was carried to [Beowulf], kind words

spoken in welcome and a wealth of wrought gold graciously bestowed.”

(Donoghue & Heaney 1168-1193)

VS.

From Chapter 8 “Farewell to Lórien” in Book 2 of Lord of the Rings:

Scene: Galadriel as Cupbearer parting with the Fellowship

Now Galadriel rose from the grass, and taking a cup from one of her maidens she filled it with white mead and gave it to Celeborn.

‘Now it is time to drink the cup of farewell,’ she said. ‘Drink, Lord of the Galadhrim! And let not your heart be sad, though night must follow noon, and already our evening draweth nigh.’

Then she brought the cup to each of the Company, and bade them drink and farewell. But when they had drunk she commanded them to sit again on the grass, and chairs were set for her and for Celeborn. Her maidens stood silent about her, and a while she looked upon her guests. At last she spoke again. ‘

We have drunk the cup of parting,’ she said, ‘and the shadows fall between us. But before you go, I have brought in my ship gifts which the Lord and Lady of the Galadhrim now offer you in memory of Lothlórien.’ Then she called to each in turn. (Tolkien 374)

AND

From Chapter 6 “The King of the Golden Hall” in Book 3 of Lord of the Rings:

Scene: Éowyn as Cupbearer in the Golden Hall

The king now rose, and at once Éowyn came forward bearing wine. ‘Ferthu Théoden hál!’ she said. ‘Receive now this cup and drink in happy hour. Health be with thee at thy going and coming!’ Théoden drank from the cup, and she then proffered it to the guests. As she stood before Aragorn she paused suddenly and looked upon him, and her eyes were shining. And he looked down upon her fair face and smiled; but as he took the cup, his hand met hers, and he knew that she trembled at the touch. ‘Hail Aragorn son of Arathorn!’ she said. ‘Hail Lady of Rohan!’ he answered (Tolkien 522)

Why draw these comparisons?

These similarities (and more) between Tolkien’s work to older texts are necessary to drawing the parallels to Grande’s music weaving and Nietzsche’s interest in form manipulation and the effect they have upon the enjoyer of the art.

Often, critics wonder, “Why would Tolkien spend so much time and effort telling such an old story?” (Sullivan 77). Yet, it is realized that “the answer lies not in the theory of the novel but… in the nature of traditional narrative–more specifically, in the purpose of traditional narrative and the intent of the traditional tale teller” (77-78). That is to explain that Tolkien’s style and purpose is intimately tied to his background as a scholar of the medievals:

“The traditional tale teller, like any traditional performer, is recreative rather than creative, doing those things that the community wants (and perhaps needs) over and over again, striving not to do something totally inventive and perceptually new but rather to do the traditional thing well and, perhaps, with some special, individual flair.” (Sullivan 78)

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings does just this; it recounts older narratives, repurposed with “individual flair”, but with intent to retain what made them magical to start.

Bardowell writes, “Tolkien prefers creation through remembrance to creation by invention” (103). He finds that “innovation is something like Nietzsche's morality… That is, an advance can only be established when it honors the ‘old maxim,’ whereas an innovation can only be accepted ‘if we are ready to scrap traditional morals as a mere error’” (103).

But Tolkien decided to now start anew, opting to remain (like Grande) tethered to older, still relevant texts (musical influences). He found, still, a purpose to the “traditional morals”, a magic that he harnesses for LotR. In his letters, Tolkien would often write “that the ideas for his mythology ‘arose in [his] mind as 'given' things’” (Letters qtd. in Bardowell 104; Bardowell 104). This displaying Tolkien’s “true spirit of remembrance, [for] he follows by claiming he always ‘had the sense of recording what was already 'there,' somewhere: not of 'inventing'’” (Letters qtd. in Bardowell 104; Bardowell 104).

This usage of old reformed into “new” but faithful in recapitulation as described by Bardowell is applicable to both Tolkien and Grande. He calls it an “art of sub-creation, which is an act of remembering or uncovering what is already there in order to build upon it. In order to sub-create, one must first notice what exists in the primary world” (104).

So, we have philosophy that is applicable to both musician and author.

For one, there is Grande–who we have seen reforms different genres of music into one nostalgic piece that evokes an impossible reality, a melodic dream.

And, of course, we have Tolkien, whose prose creates an intoxicating parallel to her music, a written world where the best of all that is found in medieval anthology is capable of existing together at once.

Both demonstrate and highlight each separate form that is incorporated into their work, applying the principium individuationis that marks the Apollonian side of Nietzsche’s aesthetic dichotomy. Yet, both music and prose are accomplished in that they display the seemingly impossible (but, indeed, possible) loss of individuation that marks the intoxication of the Dionysian pleasure in art.

~ ~ ~

Thank you for your time, dear reader…

Until Part II (which, don’t worry, will be considerably shorter) <3

Works Cited:

Bardowell, Matthew R. “J. R. R. Tolkien’s Creative Ethic and Its Finnish Analogues.”

Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 20, no. 1 (75), 2009, pp. 91–108. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24352316. Accessed 24 Apr. 2024.

Donoghue, Daniel, editor. Beowulf a Verse Translation: Authoritative Text, Contexts,

Criticism. Translated by Seamus Heaney, W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Grande, Ariana. “Honeymoon Avenue.” Youtube. youtube.com/watch?

v=_tJM74eZy04&t=0s

Klapcsik, Sándor. “Neil Gaiman’s Irony, Liminal Fantasies, and Fairy Tale

Adaptations.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS), vol.

14, no. 2, 2008, pp. 317–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41274433.

Accessed 27 Apr. 2024.

Leitch, Vincent B., et al. “Friedrich Nietzsche: The Birth of Tragedy.” Norton Anthology

of Theory and Criticism. Third ed., Norton & Company Limited, W.W., 2018.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A New Verse Translation. Translated by Simon

Armitage, W.W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Sullivan, C. W. “J.R.R. Tolkien and the Telling of a Traditional Narrative.” Journal of the

Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 7, no. 1 (25), 1996, pp. 75–82. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43308257. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

Hanh-Nhan, this is a fascinating post. I think that an exploration of Nietzsche's duality, especially as expressed in the work The Birth of Tragedy, is a fascinating way to look at Tolkien's work. One can see aspects of Apollo and Dionysus in the heroic characters alone, as various characters exhibit discipline and nobility as well as indulgence in dancing and intoxication, for example. This is a very effective approach to the text. Thanks for the interesting post!

Honey, what a truly intriguing and creative post! As I mentioned to you in person, your interweaving of Nietzsche and Tolkien with Ariana Grande on top is both impressive and surprising; and if I didn't already want to read your Substack posts (which I most certainly have throughout this semester), then this one would have definitely drawn me in. The way that you break down this particular philosopher is handled quite well for the medium you're using, and I like that you go back and forth to tie in key parts one at a time to the ways that Ariana's music works. Additionally, I think it was smart to use the philosopher and the musician together as a framework for Tolkien rather than trying to tackle LotR at the same time, so kudos to your design choices here. Thanks for this thought-provoking post!